Get your Django logs in AWS Cloudwatch

This post describes how to get Django log messages into Cloudwatch. We’ll configure a Cloudwatch log handler, and then outfit a DRF view to log a message to our Cloudwatch stream when a new object is created. This mimics a recent practical use case I encountered: Logging every request to a public API endpoint in Cloudwatch to aid in debugging. Let’s get into it!

Originally posted on Codified Musings, cross posted on Dev.to

Setup Cloudwatch — Copy AWS credentials

This post will not go into detail on setting up an AWS account. From AWS, you’ll need the Access Key and ID for a user with write access to Cloudwatch logs. I’d recommend _not_ using account you use to login to AWS. Instead, create an IAM user who we can grant Cloudwatch write access to. I tend to create separate users for dev, staging, and (especially) production environments for security and to aid in tracking down issues. At the end of the day, you’ll need to make sure the IAM user you’re using has the CloudWatchLogsFullAccess permission, and you’ll want to copy both the Access Key ID and Access Key Secret for an access key for your user (click Create access key if you need new credentials)

Configure Django Logging

We are going to override the Django Logging setting to create a new logger, handler, and formatter to get our log messages into Cloudwatch.

1. Install the python packages we need (boto3 to interact with the AWS API, and Watchtower to get push logs to Watchtower, specifically). Run pip install watchtower boto3 (you’re running in a virtual environment, right?).

2. In your settings file, instantiate a Boto3 session that Watchtower can use to connect to your AWS Cloudwatch account. In this example, I’ve put my AWS access key ID and Secret in the AWS_ID and AWS_KEY environmental variables.

3. Define new `LOGGING` settings in your Django settings file. Here’s the complete `LOGGING` settings you’ll want to add (example):

Let’s break this down.

Formatters:

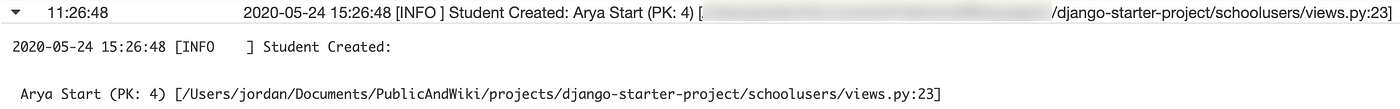

This adds a new formatter which defines how our logged messages will appear in Cloudwatch. This formatter ensures the time and log level are in the title. Here is what the resulting display looks like in Cloudwatch:

2020–05–24 15:26:48 [INFO ] Student Created: Arya Start (PK: 4) […/django-starter-project/schoolusers/views.py:23]

Handlers:

This section creates a new handler that will forward all logs of level INFO or higher, to the designated loggers (in this case, just our watchtower logger). The log_group key indicates the log group, and stream_name the Cloudwatch stream within that group, that our message will appear under. Finally, we specify the aws formatter which dictates how logged messages will appear

Loggers:

This section defines a new logger for Cloudwatch. All messages of level or higher (that is, level “INFO”) or higher, will be sent to the watchtower handler. The propogate property determines whether messages will be sent to additional loggers.

Posting a Log Message From a View

Alright, we’ve configured our Cloudwatch logger. Let’s test it out. I added the following two lines to one of my views, specifically when a student is created in my school demo project (complete source code):

I then test by posting to this view with Insomnia Rest Client. For this post, I also include example code that executes a request that uses this view, and thus should post a log message to Cloudwatch if you’ve configured your logger properly.

In my demo project, when a POST is made to create a new student, I see a message like the following appear within Cloudwatch 😀:

Enriching your log messages

I lied — the example above is not the extent of the logging I do with Cloudwatch. Because we have apps running in separate environments for local development, staging, testing, and product, we break out the logs for each of these environments to make messages easier to find (and to potentially add alarms to the production logs). In case this is also useful to you, we do this by:

1. Defining an ENV setting that describes what environment we’re in. This setting can be set from an environmental variable, or you can use a different settings file for each environment to set a different value. In our logging configuration, we include ENV in the stream_name so that each environment has its own log stream within our Cloudwatch log group.

2. We define an aws logging filter that attaches ENV to a new env property on the message. This was a key learning for me — you can use a filter to add data to a log message:

3. We use this new `env` property in the title of the message for good measure.

This is the code you’ll find in the demo code

An aside on Django Logging

As I dove into this topic, I found Django logging to be quite a bit more complex than expected. The Django Logging Documentation does a great job of explaining how logging works, how to setup your own loggers, and how to get different types of log messages to different places. Below are my notes:

Overview:

Loggers are buckets where messages (Log Records) are sent. Loggers have a Log Level (DEBUG, INFO, WARNING, ERROR, CRITICAL); Loggers ignore records with a log level below the logger’s level.

Loggers send messages (that they don’t ignore) to one or more Handlers. Handlers determine what to do with a log record — like writing to console, a file or — as in our example above — to a log repository like CloudWatch. There is a many-to-many relationship between handlers and loggers, so the same handler can be re-used across many loggers. Handlers have their own log level, and ignore records below the handler’s log level (allowing different forms of notification — based on record level — for the same logger).

I know what you’re thinking: This whole system is not nearly granular enough. Enter filters. Filters provide additional control over which log records make their way from a logger to a handler. Filters can alter the log level of a log record; they can also suppress log records based on their source or other metadata on the log record. Filters can be chained.

🤯 Big Revelation

Filters can attach additional information to log records which can then be used in formatters to customize the display. I used this feature to attach a Django setting variable (ENV) to records, so the ENV is visible in the log record in CloudWatch.

Finally, once a record makes its way to a handler and the record has a log level at or above that of the handler a formatter is used to determine how the record is written by the handler. A formatter is just a python formatting string that leverages the Log Record Attributes.

Cool? Cool. In summary:

1. Log Record created. Sent to all loggers, but ignored by loggers w/Log Level above that of the log record.

2. Filters (associated with each logger) are applied to determine which records actually get passed to handler(s).

3. Records that aren’t suppressed by filters get sent to all of the handlers on logger. Handlers ignore records below the handler’s log level

4. Handler uses formatter to determine what the record will look like when you read it. Handler writes the record (to a file, or console, or Cloudwatch, etc).